Photobomb Ghosts At Penumbra

I have a soft spot for cemeteries.

Recently, I posted an Instagram photo of a crumbling headstone and got a like from Jolene Lupo, a stranger of the alive variety.

But upon closer inspection of her profile pic—a black and white of a marble-eyed brunette—I wondered if Lupo might not be a phantom.

My sleuthing revealed Lupo was not a hallucination but the tintype studio manager of Penumbra Foundation, a Manhattan nonprofit dedicated to historical photography. The more I scrolled through her feed, the more I became enchanted with tintypes—kind-of like metal Polaroids of the mid-1800s.

As the child of antique fanatics, I grew up going to flea markets. Yet I was familiar with tintypes of whiskered soldiers, not the bearded hipsters I saw on Penumbra’s accounts.

Penumbra’s tintype of Jake Gyllenhaal created a stunning cover for a recent edition of Deadline Magazine. A headshot of Al Roker made the newscaster seem less like a weatherman and more like a long-lost uncle.

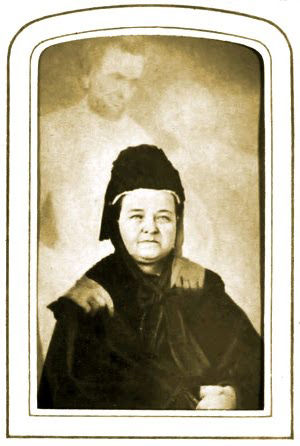

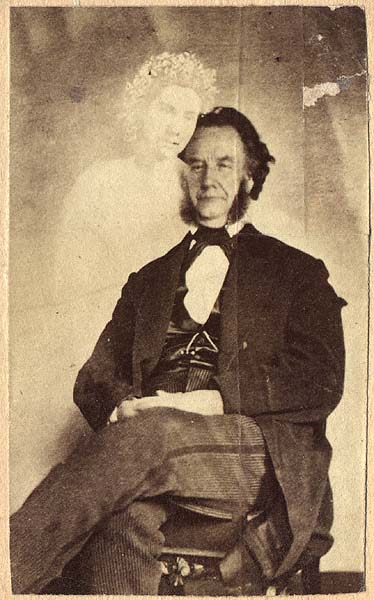

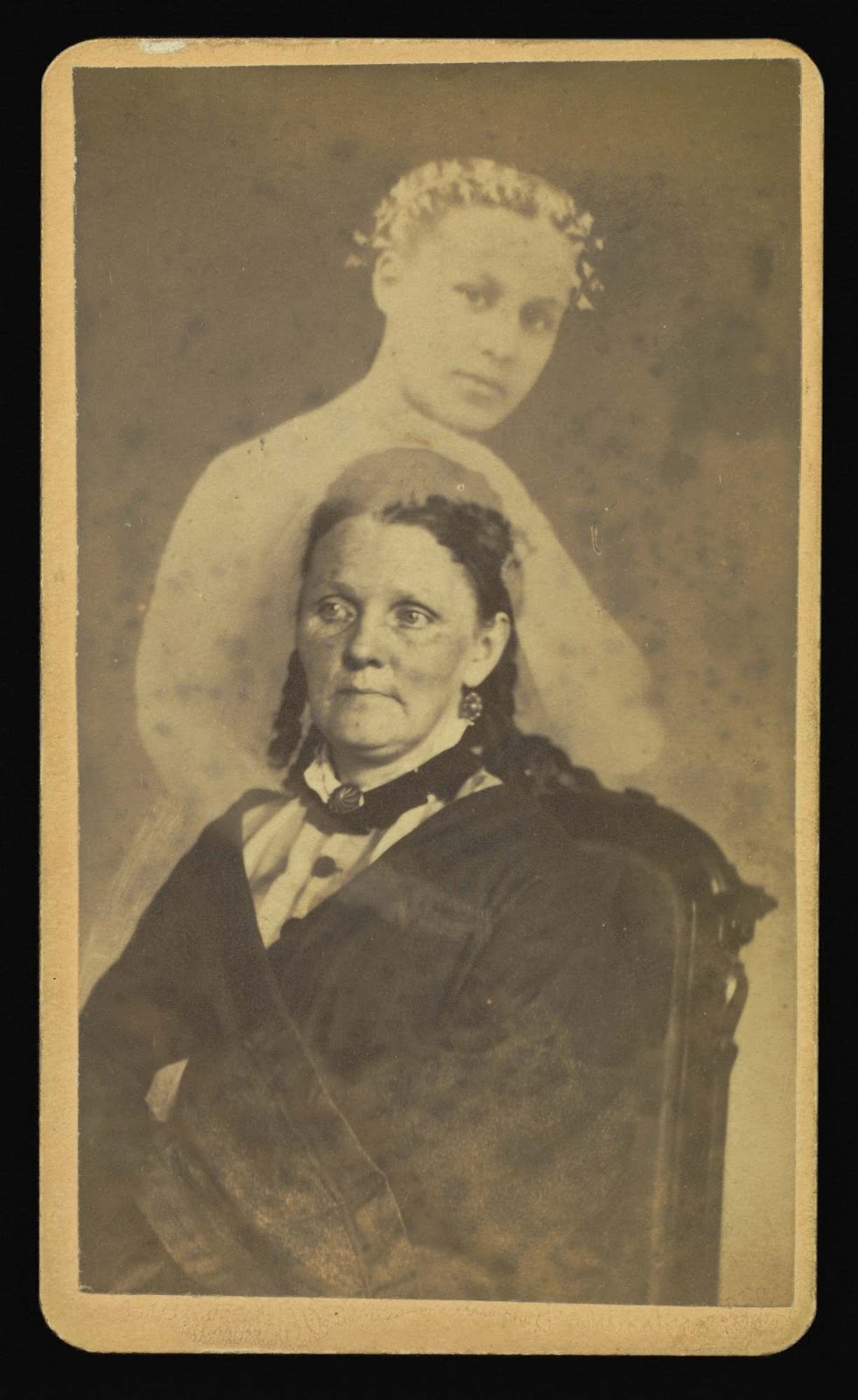

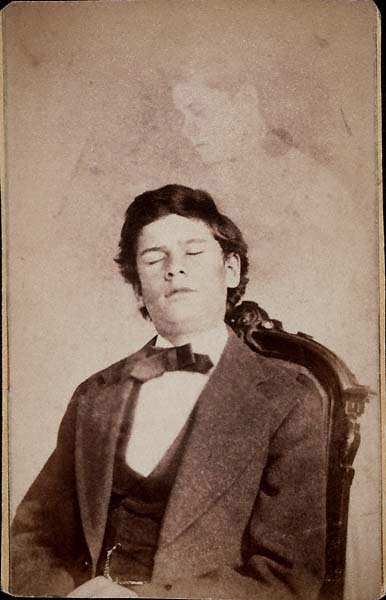

I especially admired Penumbra’s macabre renderings. Modeled in the style of William H. Mumler, a 19th-century photographer, spirit tintypes traditionally contained a sitter and a ghost, who appeared during development. Manipulated without the client’s knowledge, these tintypes claimed to connect the living to the dead.

I wanted one.

After a few days of cyber stalking Lupo and Penumbra, I became familiar with all the ways a specter could visit a single gal like me: as a ghoul in a lantern, a thirsty vampire or a bony old lady in rags. While tintype photography is enjoying a nation-wide renaissance, Penumbra is unique in that it ventures into wraith territory.

In honor of my 43rd birthday, a boring number, I decided to splurge on a one-of-a-kind portrait. With increasing pressure to feed an online personae, I wanted a keepsake that romanticized my fine lines instead of eliminating them. My goal was to have a striking profile that illuminated my soul while leaving enough shadow to protect it.

When I arrived at Penumbra’s East 30th Street location, I recognized Lupo immediately. Small-boned and dressed in black, she reminded me of Mary Shelley re-incarnated.

The studio was spartan clean with wooden floors and white walls. Lupo led me down messier corridors to glimpse relics from a massive collection: a wooden baby holder for squirmy children, an adjustable neck brace and “Big Bertha,” a canon-shaped camera with a judgemental cyclops eye.

My attention turned to the spirit photo on the wall: a headless skeleton and a present-day gentleman in a suit and tie.

But I also appreciated a scene I saw on the website, two guys in blazers whose Ouija board session was interrupted by a transparent hand.

To modern eyes, the photos are pure kitsch, but in the 1800s, clients believed.

Lupo flipped through the studio’s copy of The Strange Case of William Mumler, Spirit Photographer. The paperback showed Mumler’s most famous work: a trifecta of celebrities that included Mary Todd Lincoln, her dead son, Thaddeus, and the 16th President of the United States, who had recently been assassinated.

Mumler made a career off grief, particularly from women who had lost sons and husbands in the Civil War. Clients like Mrs. Lincoln might have been influenced by spiritualism, a Victorian movement—with roots in feminism—that offered peepholes into the afterlife. In 1869, Mumler was charged with fraud, but the jury couldn’t prove how he generated his apparitions.

“I don’t think it matters so much how Mumler did it, as much as the fact that he was able to pull it off at all,” Lupo mused, “and without the help of the internet.”

I wondered if I might also struggle between tech and reality. Certainly I was a sucker for folklore, and Lupo could spin a tale.

Her surname is Italian for “wolf.” She is engaged to a man named Falco, Italian for “falcon.”

This wolf-falcon watched my face as I produced my beat-up copy of Jane Eyre, a prop I wanted in the photo. “What do you like about the story?” she asked, obviously fishing. I told her I loved Charlotte Brontë’s descriptions of a mad first wife chained up in an antic.

After this fun interview, I changed into a 1940s robe, a gift from my cousin. I didn’t have to wear a costume, but I wanted to show off one of my most unique vintage pieces.

In the studio, we played with angles and attitude. I would look down with closed eyes—convenient, since I’m a blinker—and open my lips to convey surprise. I practiced my position, holding my book with my left hand while my right rested on my chest.

Next, Lupo led me into the darkroom to show she had no tricks up her sleeve, other than a fumey solution containing ether and grain alcohol. “Cheers,” she said, as she poured the syrupy collodion mixture onto a 4 by 5 piece of aluminum. She placed this “wet plate” into a silver nitrate bath for three minutes. By the time Lupo stuck the prepared plate into the camera, a Super Speed Graphic, I was in position. We would get one shot. The final product would be a material object she would varnish, scan and hand to me in a cardboard jewelry box.

“Look down,” Lupo said under a red and black cape. “Look up a bit more. Now hold the book in line with your chin, so it is in the light.”

Lupo took the photo with what sounded and felt like a small explosion.

Thwack.

With modern lighting and electronic flash units, the exposure was instantaneous, but finding and holding the pose made my back ache.

As Lupo went into the darkroom to wrestle with my poltergeist, I got up to stretch.

“Get ready,” Lupo called, bringing out a container with my picture floating in it.

I set my phone to video mode and watched myself emerge. I thought my lanky limbs resembled those of Granny Holloway. My shadowed eyelids reminded me of Grandma Votaw or maybe Great Granny Blair.

At the last second, there was an addition above Jane Eyre.

“Oh,” I said laughing. Then “ooooooo.” To my delight, my spirit showed itself in the form of a “mourning ghost,” a veiled woman who was so sad, she had to cover her face.

No selfie has ever satisfied me as much.

Regular 4 by 5 portraits are $100. Spirit photographs are $125. Visit here to make an appointment.

This article originally appeared in the Observer.